Part-5 Valuing Opals

Valuing Opals

To explore the area of Opal valuation further log on to https://www.opalinfo.com/#/ and get your first Opal valuation certificate free.

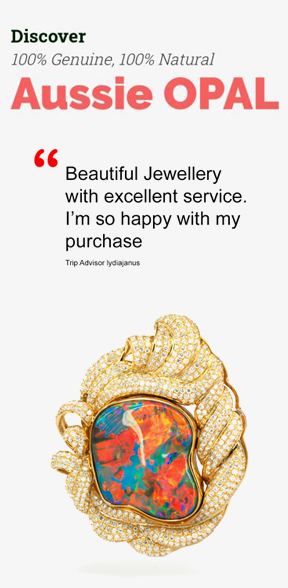

The type, colour, size and soundness of precious opal are factors that determine the price paid for the gemstone. The price is based on the quality of the opal and expressed per carat. Furthermore, there is a marked difference between the value of uncut opal compared with the value of cut and polished opal. Categories such as the variety, background, transparency, spectrum, tone, origin, distribution, inclusions, carat weight etc all add to determining the correct value of the opal itself. The clarity of the colour is critical when assessing the value of opal. Red fire is the rarest colour, followed by green/orange, green/blue and blue. Therefore red fire opal is generally more valuable than a predominantly green opal, which in turn is more valuable than a stone showing only blue colour.

However, brilliance and clarity of an open proportioned pattern are the main decision makers – a brilliant blue/green can cost more than a dull red; bright twinkling stars of a ‘pin fire’ pattern can cost more than a cloudy open pattern of similar colouration; or a brilliant, lustrous light opal can cost more than a lacklustre black opal.

The majority of us are not experts nor could we value an opal just by looking at it but there are 3 main things we can look for that can give us a clue on how valuable an opal can be:

- Multi- Directional Colour:If the opal colours change with the shift of light.

- Pattern:Large blocks of colour is the preferred pattern.

- Fire:If an opal has true fire, it will shine even in the shade

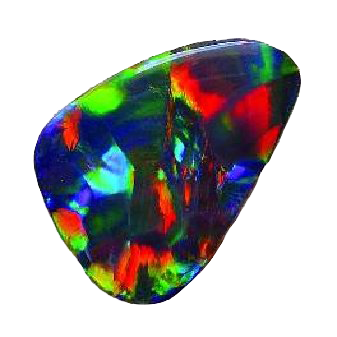

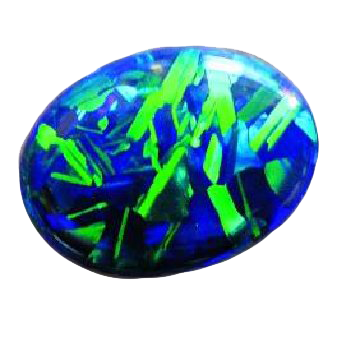

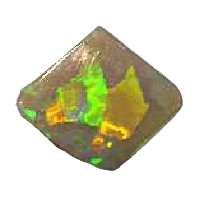

The opals shown here are 3 examples of very valuable opals.

THE HARLEQUIN OPAL

It has an extremely rare pattern like a patchwork quilt.

The Harlequin pattern is one of the rarest commercially available gemstones ever seen. Because of this any pattern that even slightly reflects this patter is highly valued. Because of this ‘blocks’ of colour are very valuable and sought after whenever they occur.

NOMENCLATURE

The use of standardised descriptions (“Nomenclature”) for Opal is considered key in establishing the correct value for the various types of Opal. For example, when a customer buys a Black Opal at some expense they need to be confident that is indeed what is widely recognised as a “black” and not a lesser stone (White or crystal Opal). International valuers have been known to confuse (or incorrectly value) Black or Boulder Opals mistaking them for Doublets due to the similarity of the Iron Oxide bars”. Some valuers even confuse the actual “types” of Opal which can affect value dramatically. Over the past few years the Gemmological Association of Australia (GAA) has worked at developing a defining nomenclature (that is descriptive naming system) for Opal. After broad industry wide consultations, the following Opal nomenclature system has been developed and is reproduced here. The Opal Association strongly endorses the use of these definitions with the aim of standardising nomenclature across the opal industry worldwide. How to best describe Opal has been a contentious and difficult issue for a very long time – and may well remain so for some time to come.

To begin with the first part of the nomenclature, mention is made of precious opal, potch and common opal. The best way of determining the difference between these is to observe whether or not the opal you are viewing shows the phenomenon which we all know as play-of-colour (compare Figs. 1 & 2). It is possession of this optical phenomenon for which opal is most prized. The differentiation between these basic forms of opal is therefore quite simple. If the opal displays a play-of-colour it is termed precious opal. If a play-of-colour is not displayed, then the opal is either common or potch opal. While it is recognised that the term precious is neither a scientific nor gemmological term, it is retained in this nomenclature for simplicity, and with the intention of further enhancing the value of opal as a gemstone by removing it from any historical association with ‘semi-precious’ gemstones. In an attempt at keeping the nomenclature simple to use, the terms “common” opal and “potch” opal have not been separated.

It must be recognised, however, that there are distinct mineralogical differences between potch and common opal. (Jones & Segnit, The term ‘solid’ has been removed from opal terminology, for the simple reason that all types of opal are essentially solid from a scientific point of view. That is, opal does not exist naturally either as a liquid or a gas. ‘Solid’ has been replaced by the gemmological term natural opal. Correlating with this use is the recommendation that when describing doublets and triplets that the term composite be used instead of ‘assembled’. This also is the terminology currently recommended by CIBJO. Essentially there are three types or forms of natural opal, which are termed simply opal, boulder opal and matrix opal. Perhaps the most contentious issue in the nomenclature concerned introduction of the term body tone, to describe the comparative lightness or darkness of an opal as distinct from its play-of-colour. Technically, it would have been best just to have two types of ‘body tone’ — either ‘black or white’ or just ‘light or dark’. However, the sub-committee rightly decided not to attempt to change too much of the terminology that had been in common use for over a hundred years. So, inclusion of the term black opal was considered to be an imperative. Following much discussion the term body tone was included in the nomenclature to describe the comparative lightness or darkness of opal — irrespective of its play-of-colour. The term tone, which is used by colour science, is in agreement with terminology used internationally to describe the lightness or darkness of particular hues or colours. This nomenclature for Opal has been designed for use throughout the gemstone and jewellery industry, not only in Australia but internationally. While preparing this nomenclature, the sub-committee has been cognizant of conventions of international trade organisations, such as the NATURAL BLACK OPAL TYPE 1 International Confederation of Jewellery, Silverware, diamonds, pearls and stones (CIBJO), the International Coloured Gemstone Association (ICA), as well as the linguistic problems associated with different languages and the differing connotations these languages may place on an internationally acceptable nomenclature. NATURAL OPAL TYPE 2 is opal presented in one piece where the opal is naturally attached to the host rock in which it was formed and the host rock is of a different chemical composition. This opal is commonly known as boulder opal.

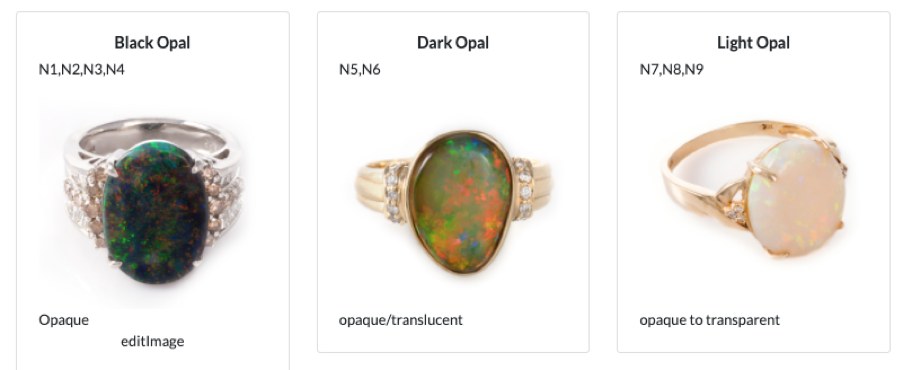

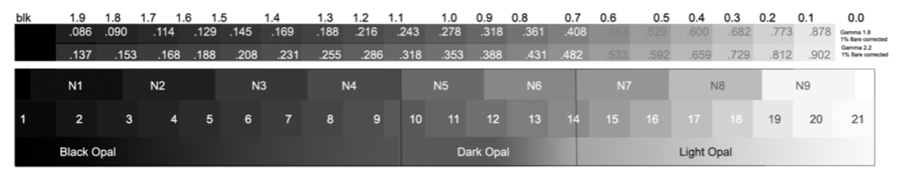

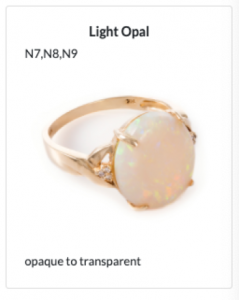

1. VARIETY

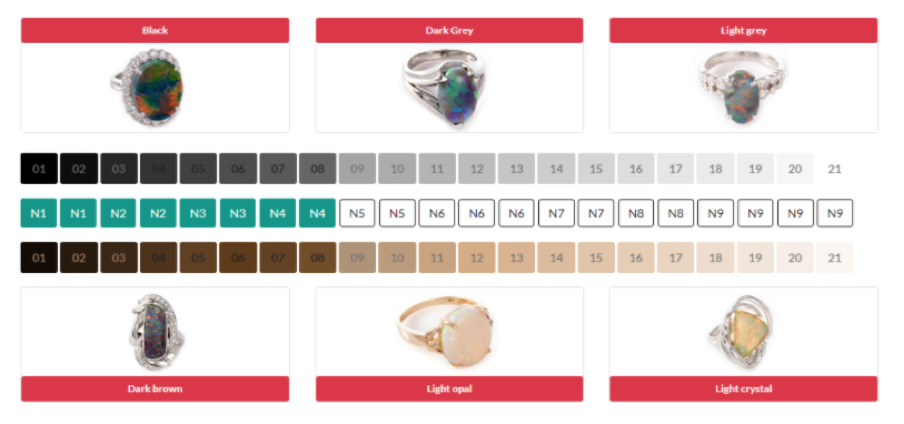

The “Variety” of an Opal is determined by where the Opal Body Tone is located within the Body Tone Chart. Opal that has a body tone of N1-N4 is defined as “Black Opal”. Opals mined in the “Mintabie” fields in South Australia have been known to produce excellent quality Black Opal however are more famous for “Dark Opal” or “semi-Black” or “Grey” Opal, terms used to describe Opals with body tones lighter than N4. Whether an Opal is a black or not can be determined by merely examining the face of the stone. All colours are ignored and the overall body tone (blackness level) is estimated. This is compared to the scale of blackness shown below stones achieving values of N1 to N4 on this scale are considered Black Opals – attracting the additional value associated of this class of Opal. White Opal or “Light” Opal is “Light” or white in appearance this is the most abundant and affordable form of Opal. Opal is hydrated silicon dioxide, which means it has a water content and an amorphous crystal structure. White Opal is the material that is also used for Doublets or Triplets which have spread in international popularity due to their brilliance and affordability. Crystal opal is pure hydrated silica it is translucent so you can see straight through it. We prefer the colour to be multi-directional, so you can see colour from all different angles, the second thing we prefer is large blocks of colour and the third thing is strong play of colour that shows up in the dark. Natural opal is opal which has not been treated or enhanced in any way other than by cutting and polishing. There are three types of natural opal. The “Type” of opal is determined by analysing the Opal is “Solid” hydrated Silica or if it is dispersed with an ironstone host.

NATURAL BLACK OPAL TYPE I

The most valuable and popular of all opals is black opal. Black opal is incredibly rare and is found at Lighting Ridge in Northern NSW, so called because in a terrible Lightning storm a farmer, his dog and 600 sheep were all killed by Lightning. It is called Black Opal because it has a black base caused by black or grey iron oxide in the opal. This black potch or common opal has no value unless we find a colour bar on top of it. The color bar or the ‘play of colour’ of Black opal comes in all the colours of the rainbow with red being the rarest and most expensive and may be designated N1, N2, N3 or N4 on the Scale of Body Tone. Black Opal has a blue-black to light charcoal body tone and is vary rarely found outside Lightning Ridge in New South Wales. The dark background serves to highlight the colour-play of dramatic spectral flashes. Fine examples of this variety are the most expensive per carat and rival rare pink and red diamonds in price. Black Opal is found as what the miners call ‘Nobbies’, these are fossil replacements of corals or sponges. During its formation, the replacement of organic material by Silica resulted in carbonaceous material or impurities like titanium impregnating the mineral structure giving Black Opal its body colour. Below are Black, dark and light precious Opals displaying a strong play-of-colour.

The natural light opal type is the family of opal which shows a play-of-colour within or on a light body tone, when viewed face-up, and may be designated N7, N8, or N9 on the Scale of Body Tone. The N9 category is referred to as white opal Coober Pedy was discovered in 1915. This is where most of the ‘white’ or ‘milky’ and crystal opals (together known as a ‘light opal’) are mined. Coober Pedy is the main producer of white precious opal, which is predominantly seen in stores overseas, particularly in the USA. Today, the opal fields encompass an area of approximately 45 kilometers. The opal level is formed of soft pinkish clay mixed with soft bleached sandstone. The name “Coober Pedy” is an Aboriginal word that translates “man in a hole” and with temperatures around 40 degrees Celsius or 100 degrees Fahrenheit all year the cool underground miners have become popular as living quarters, and now most of the locals live underground! Opal with a distinctly coloured body (such as yellow, orange, red or brown) should be classified as black, dark or light opal, by reference to the Scale of Body Tone, and also have a notation stating its distinctive hue appended to its determined body tone.

NATURAL BOULDER OPAL TYPE 2

The boulder opal is one of the rarest and most valuable forms of opal found in Australia and makes up less than 5 % of all opal mined. It is very sparsely distributed through South West Queensland. It is predicted that boulder opal is going to run out in the next 10 years because of the difficulty clearing Native Title and EPA requirements of rehabilitation. Native Title is the process of gaining agreement from the local Aboriginal tribes before mining takes place. This is an extremely difficult and time consuming process. Added to this is the EPA requirement that all mines need to be “back-filled” and trees planted when the mining is finished. This process alone can send a miner bankrupt if he has not found “colour” in his “dig”. Added to this are the onerous paperwork requirements, with “enough forms to sink a ship” the average miner just does not have the motivation to comply with all the government regulations. So, as a result there are fewer and fewer miners on the field!

Boulder opal is formed in the cracks and crevices of the ironstone boulders in a gel form possibly as recently as hundreds of years ago, and with the passing of centuries this jelly opal turned solid and as you can see we are left with some beautiful boulder opal specimens. Boulder opal occurs as a filling between the concentric layers or in random crevices in the ironstone. The cutting process is extremely difficult as the cutter must navigate the “hills and valleys” of the Boulder Opal surface. What we are left with is an incredibly unique and individual gemstone Boulder opal has a high loss factor when cutting as we only yield 5 % and has a rock waste factor of 95 %. It is also the only suggested to run out with in the next 5 to 10 years and with the value (“it is suggested”) increasing by 15-25% each year the Boulder opal can certainly make a sound long term investment.

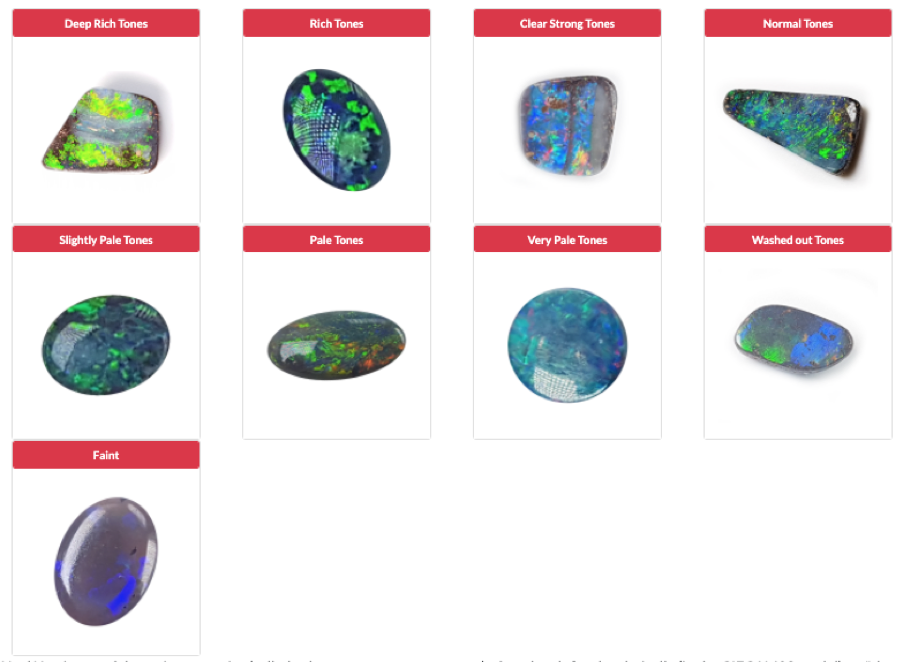

2. BODY TONE

The body tone of an opal is different to the play-of-colour displayed by precious opal. Body tone refers to the relative darkness or lightness of the opal, while ignoring its play-of-colour. To determine the body tone of an opal one examines the piece of opal, face-up, and determines (by visual comparison) its position in the scale of body tone. If the tone of the opal appears darker than N4, then the opal may be classified a black opal. Consequently, any opal with a body tone darker than N4, irrespective of hue, can correctly be termed black opal. Some boulder opal possesses this body tone, so it is very correctly termed black boulder opal. It is also appreciated that some very dark red Mexican-type opals would have dark enough body tones to be categorised as black opal. If the opal is lighter than N4, and its tone corresponds to N5 or N6 on the scale of body tone, then it is classified as dark opal. If, in addition, this opal has a decided hue colour, it is additionally classified as, for example, a dark blue opal. If, on the other hand, the tone of the opal corresponds to N7, or lighter, it is classified as light.

For more information see:

https://opalinfo.com/#/opal-characteristics

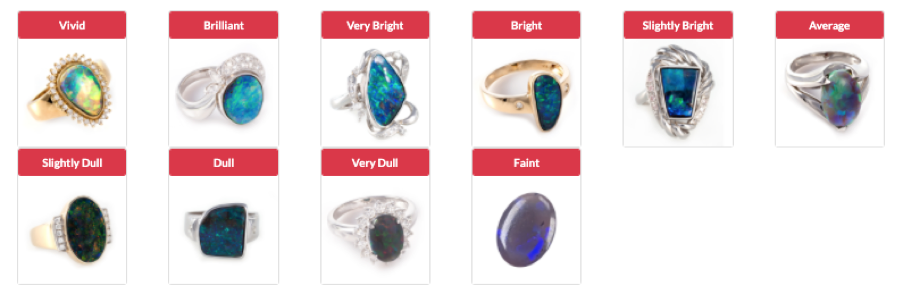

3. BRIGHTNESS

Such high regard that he departed from Rome with Vividness of colours is of paramount importance – the brightness of an Opal is directly related to price. It is not uncommon to observe several levels of brightness in the face and variation in a stone’s body tone. An assessment is made on the overall impression of a tone. One of three categories can be selected.

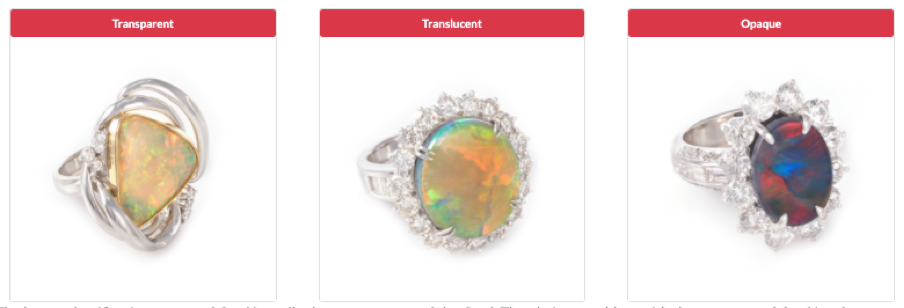

4. TRANSPARENCY

Opal shows all forms of diaphaneity that range from transparent to opaque. Natural precious opal which is transparent to semi-transparent is known as crystal opal. Crystal opal can have either a black, dark or light body tone. In this context, the term ‘crystal’ refers to the appearance of the opal and not its crystalline structure. Light Opal of the ‘Crystal’ variety is found on most Opal fields and is transparent. A dot placed on the back of a stone using a black felt pen should be clearly visible from the face. Black Crystal may be transparent to translucent when held up to the light however it is exempted from the above test due to body tone. The majority of solid Opals are translucent, transmitting and diffusing light so that objects beyond cannot be clearly seen. Crystal Opal from South Australia, particularly in red stones, may possess superior hues of rich red. However the clarity and purity of Andamooka Crystal, coupled with brilliance and relative rarity, make it the more valuable stone quality for quality. Most Lightning Ridge Crystal is cut into a pleasing high dome which enhances the depth of pattern. A transparent Jelly Opal or Crystal Opal will usually be more desirable than an opaque White ‘Milky’ Opal. Conversely Black Opals with an N1 or N2 body tone are opaque and may fetch the highest prices achieved per carat. When to term an opal a crystal opal also provided considerable discussion. The key to classification as crystal opal is really the transparency of the opal. Perhaps a better term would have been ‘transparent opal’; but any change in terminology from crystal to ‘transparent’ may take many years structure. Again the sub-committee decided that it was unwise to change a term that had been in common use for so many years. The sub-committee further believes that overseas gemmological communities may yet force a change in this usage, if strict terminology is ever to be implemented. The range of transparency considered acceptable for defining crystal opal (transparent to semi-transparent) was taken straight from Robert Webster’s discussion on transparency in his world-renowned textbook Gems. The committee decided that transparency did not need to be re-defined in the nomenclature; but just stated as a classifying category. To grade the transparency of an opal with the nomenclature, how transparent the opal is must be determined. If the opal is only translucent, then it is not termed crystal opal. It should be remembered that in some instances the play-of-colour of crystal opal will be so strong or brilliant that assessment of transparency, by the normal ‘read-through’ criterion, may not be possible as the opal cannot be ‘read-through’. When this occurs the best test of transparency would be to ‘look-through’ the opal with transmitted light. If transparency exists then this will be readily apparent. If the material remains only translucent, then it is correctly labelled as light opal. It is hoped that future scientific advances may yield a better and more accurate method of assessing transparency. A note also should be made concerning the removal of the term ‘jelly’ opal. The basic facts are that due to the extreme transparency of this opal it becomes a type of lower quality crystal opal that displays subdued low quality play-of-colour. In spite of any restriction applied by this terminology the term ‘jelly’ opal will probably remain in colloquial use for many years to come. The description of composite stones requires only a small change in nomenclature. Instead of these opals being described as ‘opal doublets’ or ‘opal triplets’, the nomenclature emphasises their composite nature by terming these doublet opals and triplet opals. In this terminology, which emphasises the composite nature of these opals, it is the first word of the term that precisely identifies the material. The rest of the nomenclature discusses opal treatments, synthetics and imitations. These are not associated with the descriptive nomenclature for natural opals but have been included to complete the nomenclature. These descriptions are in accordance with the latest edition of CIBJO’s Classification of materials and Rules of application for diamond, gemstones and pearls.

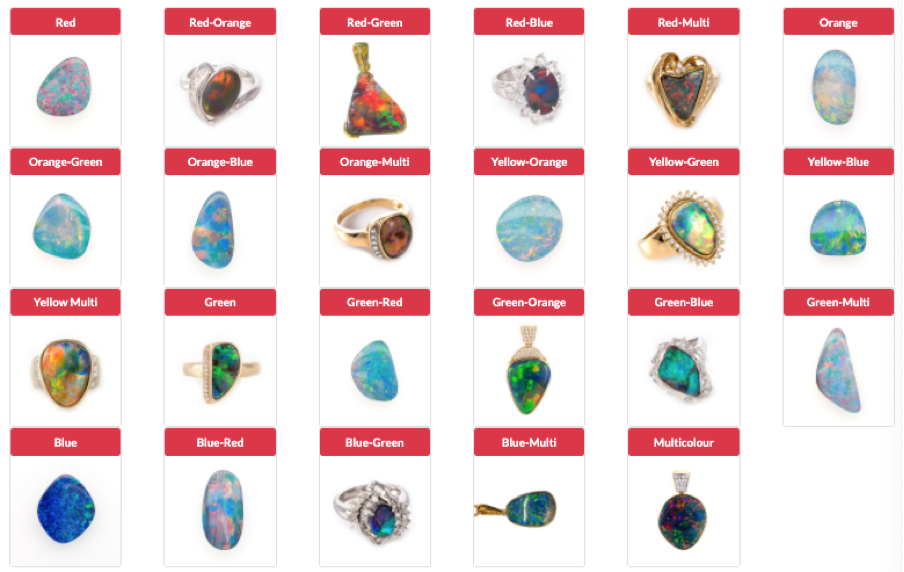

5. COLOUR COMBINATION

Colour” relates to colour “display” and how the hues are arranged on the face of a stone. When rotated through 360° in 90° segments most opals will show a marked difference at each turn. Many showing a good play of colour at one angle, can be nearly blank from one or two other angles and a price penalty is imposed dependent on the severity of the characteristic. ‘Broad’ or ‘Flash’ pattern stones often display this characteristic. Most stones look best in one particular orientation, some need to be titled to be appreciated whereas the finest Opals are non-directional.

6. HUE

Refers to the dominance of hue in the fire colour. Rich saturated hues; emerald green, rich orange etc. are always present in the finest gem quality stones yet even pastel tones if bright can make a top quality stone. Conversely subdued brightness and pale pastel hues can only indicate, at best, a commercial quality stone. The finest Opals hold their beauty in all types of light.

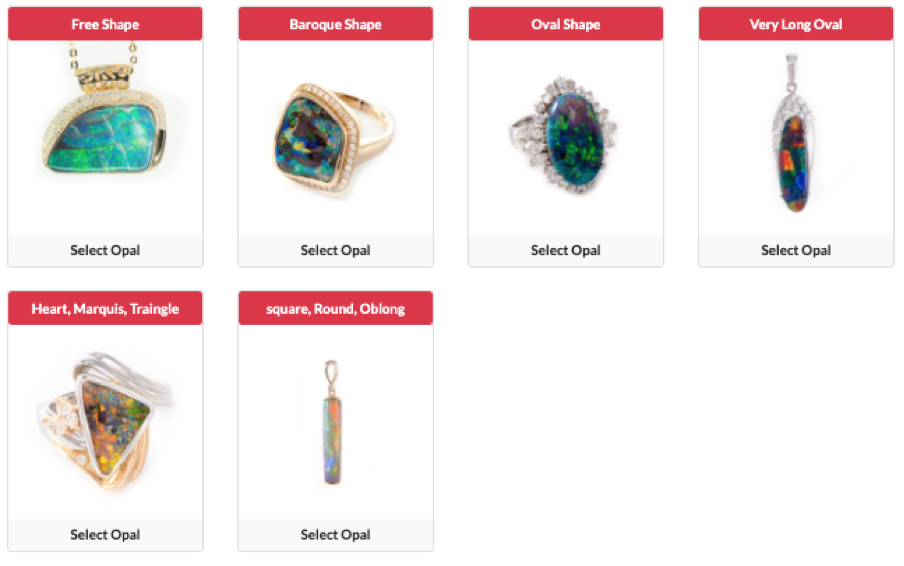

7. OUTLINE (SHAPE)

Most often dictated by the rough form. Most Opals, particularly Black Opals, tend to be fashioned as ovals and because Opal is cut ‘en cabochon’ or with a domed surface these features have traditionally been preferred for jewellery aesthetics and calibration purposes. However, most Boulder Opals are cut as free shapes which can lend themselves to more distinctive designs. In the last decade there has been a strong trend towards cutting freeform 3-dimensional shapes from most gem quality Opal. By sculpting the rough, yield may be maximised in terms of weight and spread, aesthetic talent must be applied to balance the stones’ lapidary design.

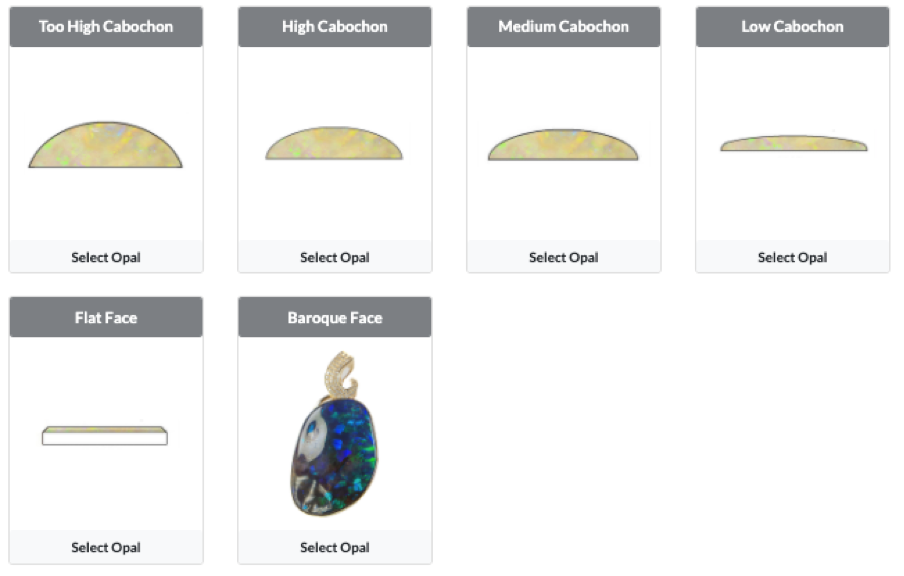

8. PROFILE

A stone with a domed surface will be more valuable than one with a flat or undulated surface. This is because the domed stone has more depth from which to emit play-of-colour. The ratio of the colour bar with play-of-colour to the thickness of potch or ironstone backing should be balanced and have a suitable setting edge for jewellery manufacture. Poor cutting and polishing will significantly reduce a stone’s value. Some stones have been cut disproportionately, a stone may have been left too thick (heavy on the potch or ironstone backside) relative to its spread or face area. Consideration is made of a stone’s proportion and aesthetic balance when determining the absolute value per carat. Any indication of the “origin” of an opal (by the use of geographical location), is not used unless it is qualified as an indication of the type of locality as recommended by the International Confederation of Jewellery, Silverware, Diamonds, Pearls and Stones (CIBJO) e.g. “Lightning Ridge type black opal”.

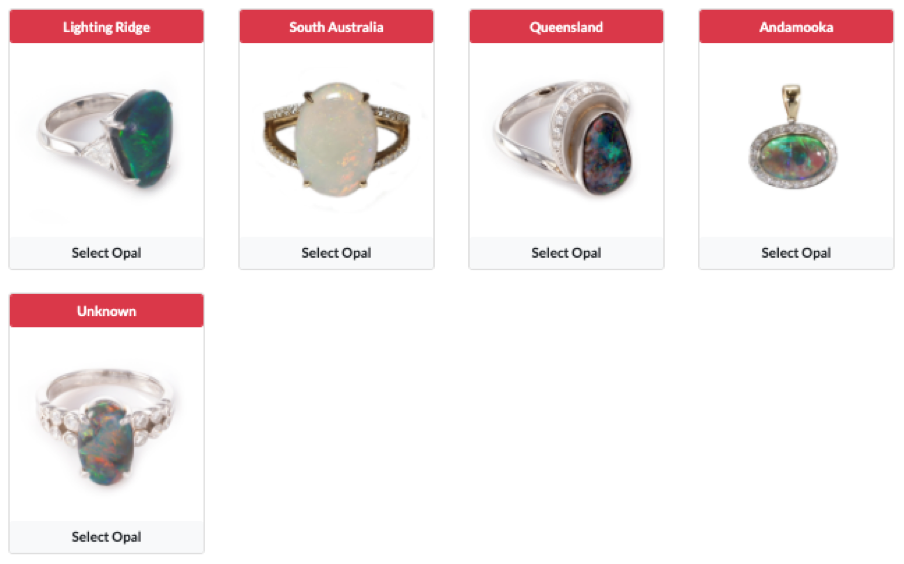

9. FIELD OF ORIGIN

The Lightning Ridge fields in far north NSW is the world’s only consistently mined source of Black Opal. Black Opal has a black or dark grey appearance when viewed from the front. The definition of the ‘tone’ of an Opal as being viewed from the front is due to the variances in colour bars that can occur throughout an Opal with the back of an Opal often presenting a different ‘body tone’ to the ‘face’ of the Opal. The black base tone is caused by black or gray iron oxide contained within the molecular structures within the opal. Black Opal “potch” (or common opal) has no value unless a colour bar is present and is often used as the backing material for Triplets (Composite Opals with three layers). Coober Pedy was discovered in 1915. This is where most of the ‘white’ or ‘milky’ and crystal opals (together known as a ‘light opal’) are mined. Coober Pedy is the main producer of white precious opal, which is predominantly seen in stores overseas, particularly in the USA. Today, the opal fields encompass an area of approximately 45 kilometers. The opal level is formed of soft pinkish clay mixed with soft bleached sandstone.

10. COLOUR OF PATTERNS

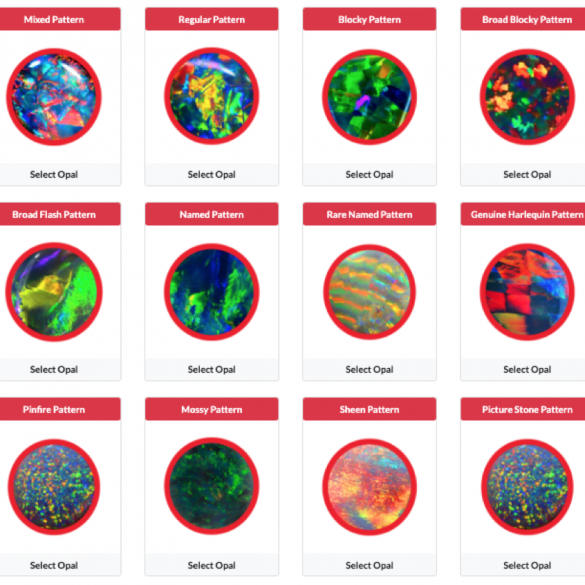

Patterns in opal are very important. There are numerous “named” patters; pinfire, broad flash, harlequin, rolling mackerel just to name a few. This is where the molecular structure is so perfect it provides a repetitive display creating a “pattern”. These “patters” are very rare and something to look for when you purchase on opal. Almost as important and when combined with brilliance may increase price manyfold. smaller pattern e.g. ‘Harlequin’ is the most highly prized pattern whereas ‘Pinfire’ is a more common pattern. The descriptions may be termed otherwise, e.g. ‘Broadflash’ may be called ‘Peacock’ pattern, and the ‘Cat’s Eye’ phenomenon is usually referred to as ‘Rolling Flash’ by the Opal trade. A vivid pattern is more valuable than a static less playful one. A lively stone possess depth or saturation of colour and pattern. While every Opal has a unique pattern, there are seven categories of patterns that all Opals fit within: Pinfire, Flash, Broad Flash, Rolling Flash, Harlequin, Rare Patterns and Picture Stones. Over 90% of cut stones have either Flash or Broad Flash patterns.

11. DISPLAY/FACE COLOUR DIRECTIONALITY (“PLAY OF COLOUR”)

‘Play of Colour’ is a unique visual phenomenon which sets precious Opal apart from all other gemstones. Also known as ‘Fire’; An Opal may display one or more, and sometimes all of the spectral colours. These colours are seen within the grains of a pattern. As the stone is viewed from different directions, rotated and tilted, the colours of each grain may change or disappear. The dominant hues in an Opal are referred to with the post script ‘-fire’ e.g. green-fire or multi-fire (multi-coloured). The spectral colours (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet – in order of value) are usually combined in varying amounts in most Opals. The predominant hue is listed first with the main secondary hue following, e.g. green-blue. The predominant hue should be at least 50% to 70% of the total fire (play-of-colour), the second or supporting hue should be around 20% or more. Some combinations are far more attractive than others, e.g. red-blue or green-blue when hues are intense, while red-orange and green-multi-fire are not as desirable. Gem quality stones with a predominance of red or orange are enhanced by a complimentary touch of vivid blue. Red Opal is the rarest and most valuable and a predominantly red stone may potentially display all of the spectral colours, if so it may be referred to as ‘multi-red’. Bearing in mind that absolute value depends on brightness, pattern and body tone; red and multi-coloured Opals are rarer than green-orange, blue-green and blue Opals in that order. Given all other factors are equal an Opal containing red can be valued greater than a blue-green-yellow Opal by a factor of up to 3 times.

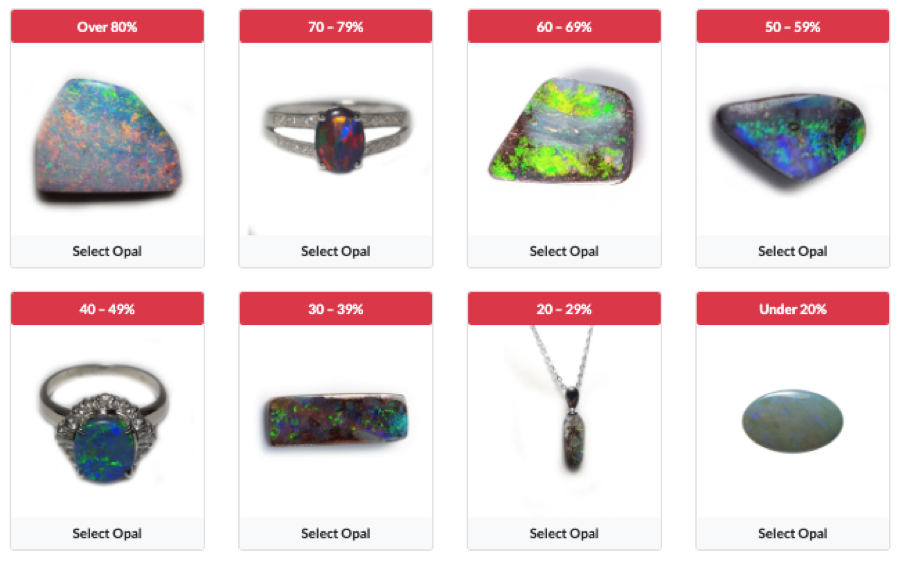

12. COLOUR DISTRIBUTION / FACE COLOR PERCENTAGE

Opal quality is markedly affected by the ‘depth’ of pattern and amount of ‘fire’ showing on the face. This factor is judged from the stone’s best angle. Very few, with the exception of ‘Flash’ pattern stones, will show 100% of the face covered in colour. Consequently a sparse ‘distribution’ of colour attracts a lesser value.

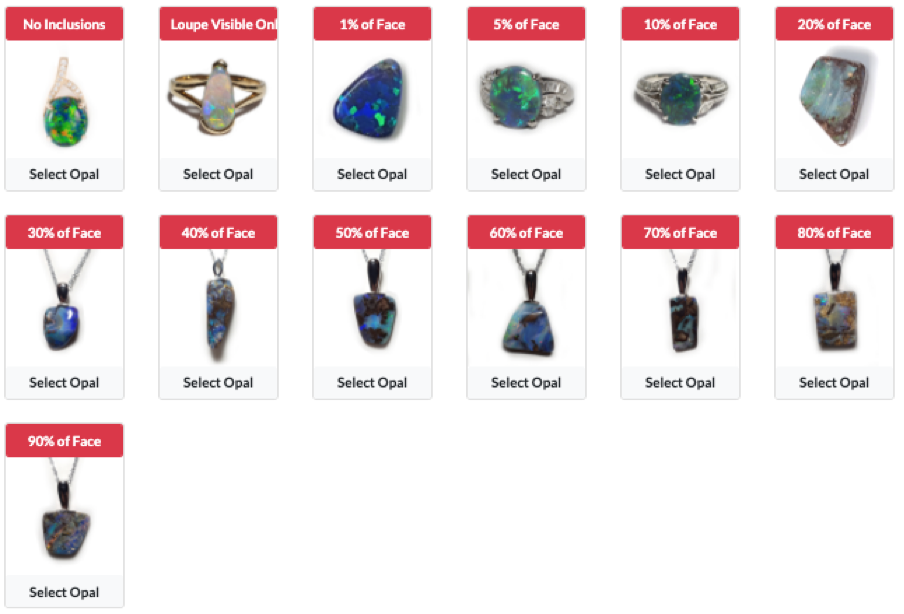

13. INCLUSIONS PERCENTAGE (FACE INCLUSIONS)

Not uncommon in the back of stones, generally these are small sand-spots and do not affect price drastically. However marks or cracks that are noticeable in the face of the stone will have a marked effect on the price of an Opal. Visible inclusions may include; patches or lines of potch, ‘webbing’, ‘sand spots’, crystals of gypsum and ironstone in the face of Boulder Opal. ‘Windows’ in Black or Boulder Opal where there is an area of transparency in an opaque Opal’s body that allows light to enter through the back of the stone and so dilute its play-of-colour are detrimental to price. Certain types of sand and othe inclusions are indicators of origin.

14. WEIGHT (“CARATS”)

Prices per carat are generally at their greatest for exceptional stones between 3 and 5 carats and up to about 10 carats, after which quality Opals in larger sizes become extremely rare and commensurately more valuable.